Living on the Edge with Mangroves

Living on the Edge with Mangroves

by Susie Hairston

When I saw that International Day for the Conservation of the Mangrove Ecosystem was coming up on July 26th my mind immediately went to the Sundarbans, located in India and Bangladesh where the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers meet and form a delta in the Bay of Bengal. The Sundarbans is one of the largest mangrove ecosystems in the world. I had read about the Sundarbans years ago in Amitav Gosh’s novel The Hungry Tide, which I highly recommend.

Before writing this article, what I knew about mangrove ecosystems was that they were a force for good – acting as nurseries for various fish and other creatures, serving as carbon sinks, stopping coastal erosion and protecting against storm surges. They are basically holding the line between the earth and the sea. I thought of them as ecosystems of the tropics and subtropics, and the majority of them are.

But, what I did not recognize until I googled “Texas and mangroves,” looking for a local angle for the story, is that we have mangroves and mangrove ecosystems on the Texas coast, and that the global problem with mangroves —the loss of mangrove ecosystems — is not the main issue for mangroves on the Texas coast.

Mangroves have adapted to thriving in harsh conditions but are threatened by human activity:

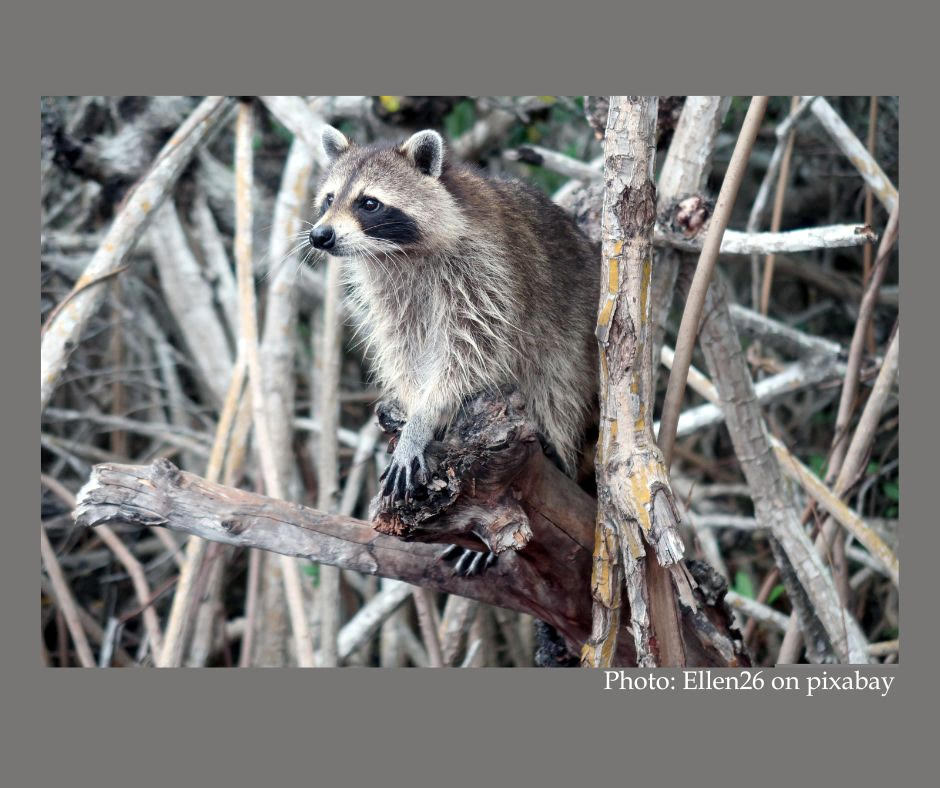

Mangrove trees/shrubs are central to mangrove ecosystems, but these ecosystems, called mangrove swamps or mangrove forests, are filled with a diversity of plants and animals.

Mangroves, because they grow where the river meets the sea, have adapted to deal with salt water. Different species of mangroves deal with the salt in the water differently. Some have a filtration system that segregates the salt that they filter away from the rest of the plant. Some secrete the salt out onto their leaves.

The water of the mangrove ecosystem is often stagnant and low in oxygen. Because of this, mangroves have roots adapted to help them take in oxygen. Some species have roots like snorkeling tubes that reach above the water to collect oxygen from the atmosphere.

The tangled mass of mangrove roots also serves to hold coastal soil in place, and provide shelter for various creatures.

These mangrove ecosystems, critical to a multitude of species including humans, fish, and birds in the areas of the world they inhabit, are being lost to a variety of factors including climate change and development (agriculture and aquaculture, the building of resorts and roads) and pollution.

“According to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural organization), some countries lost more than 40% of their mangroves between 1980 and 2005.”

Mangrove ecosystems across the world are vital to humans and other species. Because of their loss, UNESCO created a day that brings attention to their value and calls people to action to save them. And fight to save them, we should, but the story of the Texas mangrove swamps has a slightly different lesson for us.

The story of mangroves in Texas has a twist just like their roots:

According to the EPA, “In North America, mangroves are found from the southern tip of Florida along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Florida’s southwest coast supports one of the largest mangrove swamps in the world.”

The continental US is home to only 3 species of mangrove: red, black, and white mangroves,

which can be distinguished by their root systems.

The majority of mangroves in Texas are black mangroves, which often grow more inland and have root projections called pneumatophores, which help to supply the plant with air in submerged soils.

In Texas, the traditional range of mangrove swamps has been in South Texas from Laguna Madre to Port Aransas, but the higher temperatures caused by climate change have been pushing and are continuing to push their range farther north. And as the mangroves move north, they are replacing salt marshes that have traditionally populated more northern parts of the Texas Coast.

Researchers from the University of Houston, Texas A & M, Texas Parks and Wildlife Service, and various non-profits, among other institutions and groups, are studying the impacts of the replacement of salt marshes by mangroves. They are asking questions about how this will affect fish nurseries, water quality and soil erosion.

It is becoming clear that as mangroves take over, they are reshaping coastal landscapes and biodiversity. Researchers speculate that some species may thrive in the new mangrove ecosystem, while others will be pushed out. The mangrove ecosystems provide shelter and food for many creatures, but plants and animals that had been part of the existing salt marsh may not be able to survive there.

Currently salt marshes serve as nurseries for shrimp and fish, and endangered whooping cranes overwinter in Texas salt marshes. There is concern that this amazing species, which has been brought back from the brink of extinction, but is still endangered, and is the only remaining self-sustaining wild flock, will struggle, and possibly fail without the salt marshes.

Researchers are not sure whether, on balance, the shift from salt marsh to mangrove ecosystem is a good thing or not, but for the most part, they, like the creatures impacted by the northward march of the mangroves, are in accept and adapt mode.

The mangroves, like us, are living on the edge of two worlds, in challenging conditions. The message from the global community about mangrove ecosystems is that we can and must try to save them because without them we are all at the edge of open water on the brink of being submerged. The message from the story of the Texas mangrove ecosystems is that forces beyond our control, though unleashed by us, are causing great changes in our environment and in our lives. In many cases, as with mangroves moving northward on the Texas coast, we cannot turn back the tide of what has already started happening. Because of that, we need to do two things. Like the researchers, though we are under a tight deadline, we must take the time necessary to carefully observe and understand how best to adapt to the changes rather than taking impulsive action that could potentially make things worse. But more importantly, we need to act now to stop the root cause of all of this change — human use of fossil fuels —before more and more uncontrollable, and devastating change occurs.

References and resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-

https://whc.unesco.org/en/

https://www.conservation.org/

https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/

https://www.fws.gov/press-

https://www.fws.gov/species/

https://www.texastribune.org/